“How could her delicate dirge run democratic,

Delivered in a cloudless boundless public place

To an inordinate race?”

Our Food, Our Culture: reads a small green line of text under the heading Patel Brothers. It is an Indian grocery chain with dozens of locations in the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex. I squint to see it across the huge empty parking lot, pick a sunflower for my hair, and walk into the interview. I have quit my job at Kumon for this. Prithi Singh was appalled that I was going to work at a steakhouse, it was such nasty work, and she offered me fifteen dollars an hour to stay. But here is what Kumon was like: I said umbrella, umbrella, umbrella on a daily basis and pointed to the word on the soft gray consumable page. Then a three year old Indian girl with a Buddha-fat face stared off into the ether and said oombraylah. The whole thing seemed hopeless and immoral.

Clayton is six foot three, in his early forties, and handsome in a safe, center-right, nondenominational youth pastor type way. He looks like he could be a Dave Ramsey personality, like he will judge me on the firmness of my handshake. He will not be doing the interview. Instead it is Brooke, a plain woman in her late twenties who comes out ten minutes later with a clipboard. I have been studying the caricature of Dolly above the opposite booth. Brooke asks me several hypotheticals about customer service, checks my availability, and tells me to show up at four next Sunday for orientation. I ponder the hypotheticals. What if a customer tells you their meal was unsatisfactory? Correct answers: alert the manager, say you’ll make it right. These seem so obvious that the wrong answers become fascinating. When I was fifteen and applying online to McDonald’s they made me take a personality inventory. I wish I had failed it.

By day I am engaged in aristocratic pursuits like learning what an anapest is, and thereby making myself obsolete relative to the tech Indians. My advisor Dr. Chambers was a scientist before he studied poetry, and I take comfort in this. He explains the loosening of poetic form in this way: that in preindustrial times poesis proved you had a human mind, the intricate regularities of craftsmanship evidenced consciousness. But for the past two hundred odd years machines have been more precise than we are, and they can beat us all at chess, and soon they will be gestating and practicing law, so poets decided that the best assertion of one’s humanity was to screw things up. He is a disciple of Wallace Stevens, and has a moneyed old Boston accent and pointy little blue-black eyes. In his presence I feel the masculine urge to learn coding, to articulate nuance and to make myself immortal.

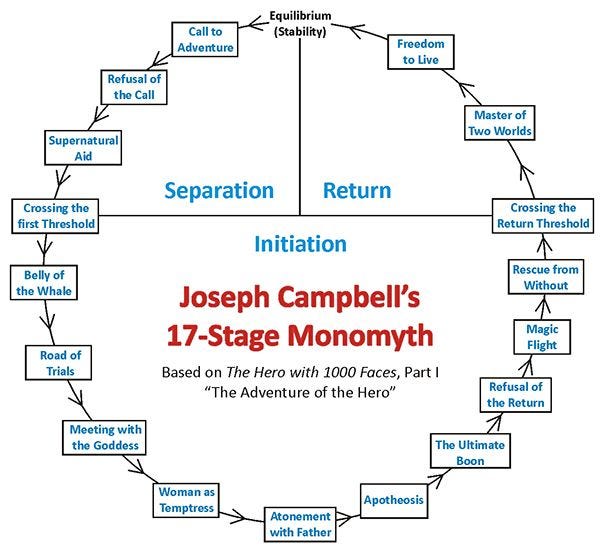

Then there is Father Daniel, the ancient Cistercian, who used to have dinner with the Fugitive Poets, and who calls me Hera and not my name. He teaches Southern literature and I think he really believes in the collective unconscious. On this particular day he is diagramming the Hero’s Journey on the chalkboard, drawing a trembling circle, staring off at the blazing elm trees with mucused priestly eyes. Then, as if possessed, he stands up from his chair and and blusters:

O Western Wind when wilt thou blow

The small rain down can rain?

Christ! My love were in my arms

and I in my bed again.

This is real poetry, he insists without explaining, and goes back to scribbling refusal of the call.

By night I ponder the issue. I wear black non-slip boots and I wade in them across the soapy tile, and peanut shavings float on the water. I scrape mounds of kraft mac and cheese and briny green beans and whole ribeyes into the wheely black trash can. I introduce myself constantly, field complaints about steak doneness, roll silverware, upsell shots of Grey Goose and Jose Cuervo. When someone claims to have a birthday I drag over the saddle and make them sit on it and wave a napkin frenetically in the air. Then I give the following speech: Attention Texas Roadhouse, we’ve got a birthday in the house! (Name) here is turning (age, not to exceed twenty one). I want you to stop what you’re doing, swallow what you’re chewing, and give me your loudest, proudest, Texas sized yeehaw! One, two, three, yeehaw!

For the purposes of this little speech I fake a light accent. This is for fun but also so my voice can cut through the country music which blares out of every wall at ninety decibels. After the place closes I wipe the rims of ketchup bottles and wash the nipples of the soda machine, for $2.35 an hour since I am not getting tipped. Finally when I check out on the POS system, a menacing little graphic of Andy the Armadillo pops up on the grainy screen. He has a red bandana around his neck and a badge and hat like a Texas Ranger. Under-reporting your tips is a crime, he says. Would you like to revise your tip amount? He will not let me enter zero, so I put in some low-ball number, and he is mollified. Andy is a stabilizing, sunny, neoconservative presence–like Ted Cruz, a target of mild but constant ridicule. I walk to my car with a hundred dollars cash in hand. The air is wet and smells like restaurant, and the highway interchange below me coils like a ceremonial knot. It’s an hour to Oklahoma–I think I should just drive.

I was on keto recently, and I am thinner than I have been in my life. It seems to me that I am pleasing the ancestors–the dryland ranchers and the Vikings, and as I read Genesis for academic purposes I become convinced that grain destroyed liberty. God rejected the offering of the farmer Cain, whose descendent Tubal-Cain built the first city. And he threatened the Israelites thus when they begged for a king: your sons will be cannon fodder, your daughters will be perfumers and bakers. Your daughters will be bakers. Esoteric beef doctrine equates the feminine with yeast. Yet to me the sincere feminist if she exists must be a luddite, a degrowther–the city and the harem arose at the same time in the same fashion. There is a short Hispanic woman who stands apart, making the famous yeast rolls and cinnamon butter, and she looks irritated when we waitresses hover by the chilled steak display case waiting for roll baskets–right now it is me and Beth. Clayton told us to wear costumes for Halloween tonight, but Beth’s is not family friendly. I guess she doesn’t have much to gain from obeying. She is only here on weeknights, Friday through Sunday she works at the Hooters down the road. Her drawl is thick for a young person, her hamstrings are perfect, and her face is pretty and strong. I think I fucked up, she tells me. It turns out the Hispanic family in the corner showed up with a Walmart cake for their daughter’s birthday, to be brought out after dinner, but Beth has given it to the black family a few booths down, and now they’re eating it like nothing is wrong. Beth refuses to show her face in that section of the restaurant. I march off to the Hispanic family to explain the situation and offer them free brownies– they are kinder than expected, and for some reason the patriarch of the family slips me a ten dollar bill (all the while I am thinking redacted thoughts–this town has made me a monster).

He will take your sons and make them serve with his chariots and horses, and they will run in front of his chariots. One day after class I tell Chambers about my fiance’s observation that in Kurdistan, people actually read poetry. I ask him why he thinks this is, and his answer is that Americans refuse to think. He wants to know, however, what this fiancé does in the army, and whether he has a job that allows him to use his mind. I am not sure what to say. The man is all chest and heart, all thumos, though the recent pictures in the FRG group chat show him looking eerily thin and puzzled. It is fall in Texas now (is there fall in Kurdistan?). The air is less sweltering and sometimes it rains so heavily the walls shake and the smell of peanut oil leaves the air. On Sunday I get off work and go to the huge Kroger on Macarthur and buy eighty dollars worth of orange construction paper, candy corn, turkey-jerky, and sage scented deodorant. Then I come home and put on sweatpants and spend the evening putting together a Thanksgiving gift box. I hope it will get there in time. My Indian roommate comes in from the lobby, chattering about that K-Pop group with more members than a state senate. She has been coding all night by the bloodshot look of her eyes. She is kind and goofy, her knee-length black hair swings in a braid behind her, and she has beautiful little ankles. She insists to me that all religions, at their core, are one. Her diet consists mainly of samosas and potato chips, and she has slipped in the shower three times and broken the same femur. I like her well enough but I don’t want to explain myself to her. Compulsively I check the gift box for booze and pork and imagine some Iraqi censor opening it, nibbling the candy corn, and shittily taping it back up again.

If you were to construct for yourself a mythology of Texas, you would like to believe that the crippled governor got that way in Vietnam, stepping over landmines in the jungle, or perhaps in a drug-related shootout in the desert. In fact he was jogging one day after a rainstorm and a loose branch fell on his legs and he sued the homeowner whose tree it was. The steel rods put in afterwards are not machine guns, but I wish they were. In this ignoble weakness Greg will not even pretend to walk for the media like Franklin D. Roosevelt did–you get the sense he is almost proud. There are some men in whom fat takes on the terrible appearance and almost the function of muscle, and Texas is like this. When I moved here I started watching King of the Hill and if I squinted I could still see its faded white and green frames. That humble ranch style home still fills the Mid Cities. But now there is more than one Laotian neighbor, and Hank is seventy and he comes tottering in on a walker every day and tipping eight dollars on a twenty dollar check and leaving. When I see men this age I feel a childhood urge to thank them for their service, which I must consciously repress. But the instinct has a place in Killeen. That is where I left him, in that other Texas with its long drag of strip clubs and pawn shops and storage facilities, its cheap Korean restaurants run by grumpy old war brides. Its fake village designed to look like Iraq, and another designed to look like Russia. I left him at the gate near the Iraqi village, with the creek bubbling and a hawk circling over the shallow canyon.

I am convinced that moderation is a great artistic and political sin—good art is a reconciliation of extremes. Think for example of the unforgettable sentence Francesca da Rimini is a slut– the whole effect comes from the contrast between the Italianate name and the low Germanic slur. It forms a gestalt which sticks like a sunspot to the back of your eye- an ionic bond not a long deliberation. On the other hand Margaret Atwood is gifted and possibly subgenius, but the Penelopiad is an awful book and reads like a Reductress article. I am not interested in twenty years worth of intrigue and wry observation, or in the fact that the servants were actually slaves. No–the Odyssey was good enough for both Odysseus and Penelope and all the slaves beside. Half a poem is space, and you can feel her spirit moving in his aristaia, silent like an underground river. Every marriage consists of an aristocrat and a peasant, and this is just and right. Soul and soil are opposites but so close as to be one, and the fiddle and the violin are the same instrument.

The country music which can embody this is great, but most of the genre is garbage. This is the general opinion of the public, and my time at the Roadhouse confirms it. I watch YouTube videos about country’s decline, where they run analyses of the most common words in the hit songs. You would think they would be words like “beer” and “truck” and “girl”. This is the redneck-negro hypothesis, that rap and country are two species of the same genus, that blacks and poor whites hate each other because they are too much alike, and are both justifiably hated by the broader Teutonic culture. An extreme example of this is “Body Like a Back Road,” which I will not quote here and which plays at work probably twice an hour. But it turns out that the most unique (or disproportionately common) word in country music is “little”. A word that softens everything it falls on into a nostalgic haze. A little drink, a little lovin’, a little one-horse town. A small city where late into May a frost can hang on the gold valley, and the ranchland comes right up against the new development. When I was a little girl there my mother would take us to Texas Roadhouse and pay for each of our Ranger Meals with a circular wood token she had gotten from a Church festival. We did not know anyone in the Iraq War, and I never had a thought of living in Texas. What brought me to Texas was the hope of rich stories, not to be found in the clean cold liberty of the Denver exurbs. In Colorado, history had gone from its savage phase to its democratic phase almost instantly. Indians, then suffrage, then Columbine. But in Dallas, a thousand miles from my family, I would meet people of merit and we would sit up late and get drunk and recite Homer.

This is what I got for it. I recognized now in myself the same hideous impulse below the Nation and likely the whole West. It has turned me tricorn and monarchist and back, the homesick westward drive, the love for the foreign-made flags on the pale smooth twigs coiled in the Walmart bins like ribbons. The instinct behind this:

“And I’m proud to be an American

Where at least I know I’m free

And I won’t forget the men who died

Who gave that right to me

And I’d gladly stand up next to you

And defend her still today,

For there ain’t no doubt I love this land,

God Bless the USA”

But what you may not understand is that, when you hit the high note on stand up, you need to scream it, you need to arch your throat and yodel, you need to shriek it like your life is ending. Our anthem is the same. It is not suited to the normal human voice. There is an extant clip of some Walmart people in Haslet, at the northern edge of the metroplex where the density is low enough for a Buc-ee’s, all stopped spontaneously in the aisles one summer to sing the national anthem, most of them badly. But one birdlike soprano rings among the others, sings free legitimately and does not botch it, and it makes you wonder.

Veterans day is coming up, Clayton informs us. It will be a Monday but we will open at 11am. You cannot ask off for Veterans Day and if you are scheduled you have to come. Active duty service members and honorably discharged veterans may receive a free meal of their choice from the Special Veterans Menu, which includes among other things the chicken fried steak, the all American burger, the six ounce sirloin, and the chicken critter salad. Proof of service includes military or VA identification card, or discharge papers.

this is marvelous. I went to UD too. I felt it in this.

Everything is gutted--replaced with a sorry imitation. Country music so often substitutes petty sentimentality for the strong, rolling emotions. Certain older songs like The Thunder Rolls (Garth Brooks) or The Night the Lights went out in Georgia (Vicki Lawrence, Reba McEntire arguably better) give a real punch. Anyone in country still write songs like that?

Problem is that we're spiritually diminished. Default promiscuity dilutes the sting of adultery, though not the impact, of course. Likewise, the judicial is so detached in the big cities, we can't grasp the idea of small town personal justice gone wrong without turning it into a caricature. We are entirely inward facing--seeing only ourselves.

If you're old enough, you'll remember the promise of a new America after 9/11. Happy anniversary! We were going to unite. Put our differences behind us. Crush those who seek to take our freedom! That's what Proud to be an American is about. People really believed it but it didn't take long before one political wing decided that the real threat to the country was anti-Muslim discrimination and the imminent Christian theocracy (lol). Of course, the War on Terror was ridiculous from the start. There was no vast Muslim conspiracy poised to bleed the nation with a thousand cuts.

"Where at least I know I'm free"

What does "free" mean, Mr. Greenwood? Opinions vary. If you pressed the people who listen to country music, they'd probably come up with something like "the vote" or "not having to tack the leader's portrait on my wall." The people people who ostentatiously dislike country music interpret "free" as "public celebration of sodomy." Trying to paper over a difference like that with sentimental descriptions of the landscape didn't work. Both ideas of freedom are incredibly stale. They barely mean anything.

I appreciate never having been compelled to put George Bush's portrait on my wall but that doesn't seem a right worth dying over. No one feels that way.

But no one wants to live this horrible spiritually impoverished life, so we're always larping the lost past. You can't be a monarchist. There's no monarchy. You can't be a patriot. There's no country. You can't be a brave antifa fighter in the resistance. There's no tyrant.

All the fakery gets tiresome.